How Edison illuminated Newburgh

On Monday, March 31, 1884, the citizens of Newburgh found themselves on the cutting edge of history.

That afternoon, the steam boilers at the new Edison central power plant on Montgomery Street were fired up, and as dusk settled on the city, downtown merchants switched on their electric lights for the first time. And so, just five years after Thomas Edison perfected his design for an incandescent light bulb, and 18 months after the first-ever central power plant opened on Pearl Street in Manhattan, Newburgh became one of the first U.S. cities to be electrified.

“During the early part of the evening throngs of residents gather on the sidewalks in front of places of business to inspect the light,” wrote Reese V. Jenkins in “Edison’s New Light for Newburgh,” published in the Orange County Historical Society Journal in 1984. Hardware store owner Charles J. Lawson painted his shop walls white and cleaned the display windows to better show off the new lighting. Another center of attraction is the store window of the jeweler, W.H. Lyon. "His small store is illuminated by seven lamps," wrote Jenkins. "The sight is magical with the glittering reflections in the display cases full of elegant silverware.”

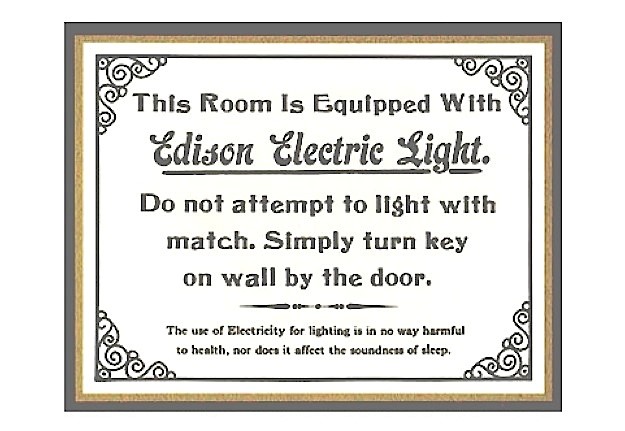

That evening there were 40 businesses with a total of 200 electric lights in operation. And while the new Edison lights were of great fascination to the citizens, interior lighting using lamps powered by a centralized distribution system wasn’t a new concept. Gas lights, using manufactured gas derived from coal and delivered via underground lines, were used for both street and interior lighting from the mid-1800s on. But gas lights had several drawbacks; they created soot, could cause fires or asphyxiation, were of limited brightness, and had an inconsistent, flickering flame that could cause eyestrain when reading. An earlier form of electric light, arc lighting, generated illumination through the arcing of electricity between two carbon electrodes, but the light was very intense — useful only for outdoor lighting or very large indoor spaces — and the components had to be replaced frequently. In comparison with the options available up to this point, the incandescent lamp Edison and his associates had perfected after years of frenzied work in Menlo Park was warm, pleasant, constant, safe, and clean.

The new electric lights took some getting used to.

“As people gather,” wrote Jenkins, “they freely comment and compare the electric light to gas. Some are surprised that it is not more brilliant than gas, while others speak of its warm glow. Some note how stead the light is without the usual flicker of a flame and they expect therefore that the electric light will be less tiring for the eyes. Overall, everyone is very impressed with the new Edison lamp.”

View of Newburgh from across the river.

Why Newburgh?

The Newburgh of 1884 was a thriving commercial and industrial city. It served as a transfer point for freight and passengers traveling north and south on the Hudson River and east and west on the railroad. An account of the city’s centennial celebration published in the Newburgh Daily Journal the year before described it as follows:

The present city of Newburgh equals in size any city on the Hudson between New York and Albany. Its only rival between the Metropolis and the Capital, in the number of residents, is Poughkeepsie, whose population of twenty thousand it now equals, while it surpasses Poughkeepsie in commercial advantages, means of communication with the rest of the world, present growth and business activity, and in prospects for future prominence. No city on the river approaches it in lowness of taxation. No place could be more healthfully located. Its people are industrious and law-respecting, and it is inviting alike as a place of business and a place of residence.

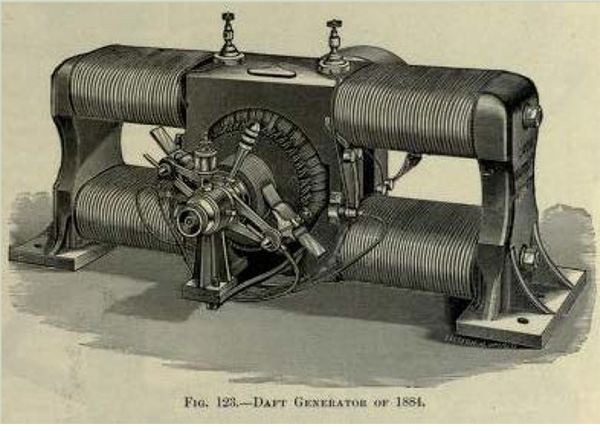

In addition, Newburgh was an early adopter of Edison’s electric lighting, with two large mills installing on-site generation (called Edison isolation plants) in 1881: The Orange Woolen Mill on Little Britain Road (126 lamps) and the Newburgh Woolen Mill on the corner of Little Britain Road and Wisner Avenue (60 lamps).

A dynamo of the type that was installed in isolated plants in local factories.

The Orange Woolen Mill. (Photo courtesy of Newburgh Free Library: Nutt's History of Newburgh)

Both were in operation before Edison launched his first central generating station on Pearl Street in September of 1882. That station was a proof of concept, delivering uninterrupted power to customers within a one-square-mile area of lower Manhattan. These examples inspired a group of Newburgh’s leading citizens to lobby Edison to build a station in Newburgh.

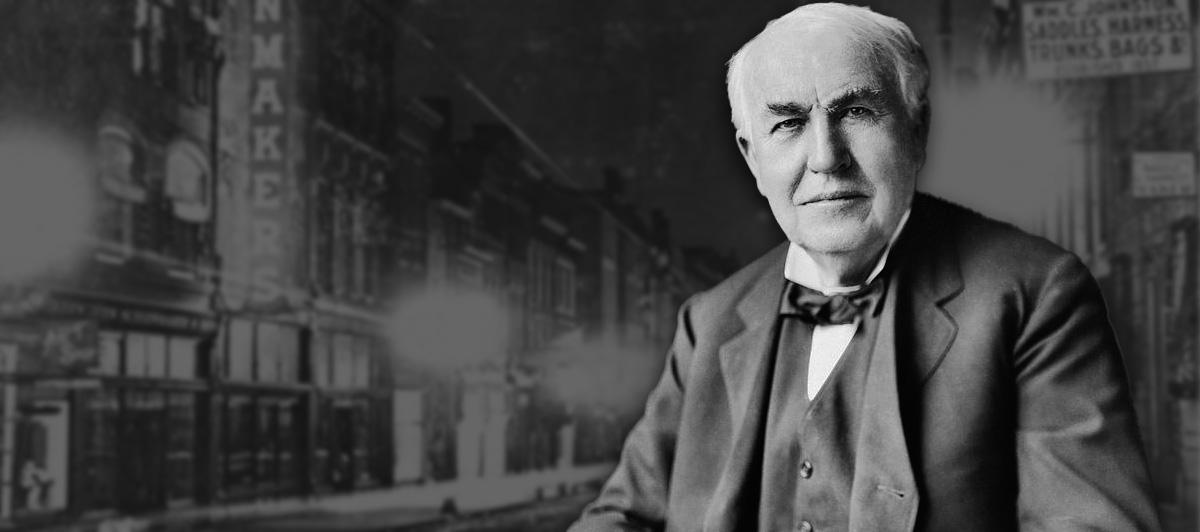

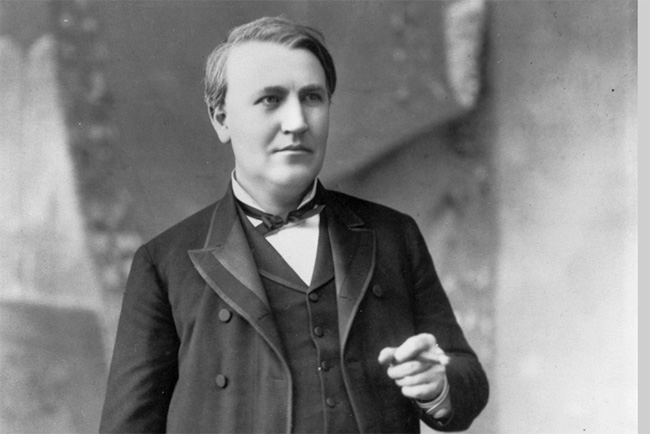

Edison as he appeared in the early 1880s.

Making it happen

It’s worth pausing here to note that in addition to creating the first long-lasting and reliable light bulb, Edison also had to invent every component of the electrical distribution system, including meters, switching systems, distributors, fuses, junction boxes, and more. Completing this work took over three years and involved somewhere between 200 and 300 patents.

After all the pieces of the first electrical grid were in place, Edison pried himself out of the laboratory and set about bringing electricity to the people. Already famous for the invention of the phonograph in 1877, Edison’s subsequent activities naturally attracted public interest. In a March 13, 1883, newspaper article under the headline “EDISON AND HIS LIGHT – The Favorite Son of Port Huron Will Confine Himself Solely to Business” the “Great Edison” said: “I am going to be simply a businessman for a year. I am now a regular contractor for electric light plants, and I am going to take a long vacation in the matter of inventions. I won’t go near a laboratory.”

It was during this time that Edison and his associates fanned out to establish central stations in communities in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Newburgh. In late 1883, Edison agent Charles T. Hughes made the trip up the Hudson at the invitation of local champions of electrification, including Horatio B. Beckman, part owner and superintendent of the Newburgh Steam Mills, John P. Andrews, a successful construction contractor, and Moses C. Belknap, president of the Highland National Bank and a local soap and candle manufacturer. Still, the new station and system weren’t an easy sell. Hughes wrote to Edison, “I never saw such hard scratching to raise a little money as it is here where plenty of people have lots of it.”

Aerial view of the electric plant on Montgomery Street. (Central Hudson archives)

Inside the Montgomery Street station. (Central Hudson archives)

But eventually, sufficient capital ($45,000) was raised from local investors and the Newburgh Common Council’s approval was secured. On October 29, 1883 Edison signed the formal agreement and the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Newburgh was formed. After that, work went quickly. The company constructed a building on Montgomery Street for its generating facility and purchased an existing brick house nextdoor to use as an office. The coal-fired steam boilers were installed in January and underground distribution lines were laid and businesses wired in late-February. By the end of the next month downtown Newburgh became the second city in New York State to be illuminated with incandescent light. It took just five months from the formation of the company for the city to have a working power plant and distribution system; a timeline today’s engineers could only dream of.

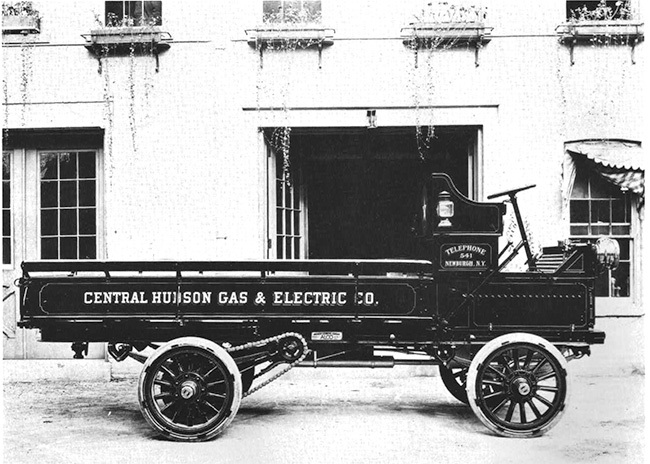

An early Central Hudson service truck. (Central Hudson archives).

Competition and consolidation

Soon, Edison’s men turned the station over to a local superintendent and moved on to spread the gospel of centrally generated electric power to other communities. By the late 1880s, more than 180 plants were operating across the country.

In Newburgh, a rival arc lighting company was formed in 1885 to provide streetlights. Also by the 1880s, the city had two gas companies: The Consumers Gas Company and Newburgh Gas Company, both of which initially competed for lighting customers. The electric companies merged in 1895 and later absorbed the gas companies to form Central Hudson Gas & Electric in 1900.

The original Edison power plant is still in use by Central Hudson as a substation.

And while both the Pearl Street station in Manhattan and the famous Menlo Park laboratory were destroyed by fire, the Newburgh station is not only still standing but is still in use by Central Hudson as a substation. A plaque at the site was dedicated in 1929 to commemorate “Edison’s invention of the incandescent lamp and as a tribute to those citizens whose enterprise made electric light available at its inception for use of this city.”

Sources: In addition to “Edison’s New Light for Newburgh,” by Professor Jenkins, we also drew on slides from “Electrifying Newburgh,” a presentation by Professor Paul Israel, general editor of the Thomas A. Edison Papers Project at Rutgers University.